Niklas Taleb at Cell Project Space

'YOLO': the exuberant calling card of the early 2010s, popularised by Drake's mixtape of the same name, preceding The Motto, a real guilty pleasure track featuring Tyga and Lil Wayne in 2011. The phrase became exactly that: a motto, and an often tongue-in-cheek way of life, anchored in a time that felt comparatively simple. Perhaps this is what internet culture is, and always has been: jumping on popular trends regardless of your social status, cringing all the while, before the amorphous blob of content and satire becomes so murky that you have no idea whether you actually participated in the homogenous activity (spoiler alert: you did). Is this the social life of the platform age?

In German artist Niklas Taleb's solo exhibition, Solo Yolo, at Cell Project Space in East London, we are reminded of the motto's privilege. In its heyday, 'YOLO' was said frequently prior to doing something vaguely courageous, daring, or spontaneous; the "fuck it" of one very specific moment in recent history. There's a real feeling of leisure and relaxation in the works, which have been curated with a satisfying distance between the respective images, reinforcing the hazy days of simply caring less. Perhaps this hazy lack of caring is long-hand for 'youth'. One cannot help but wonder if the next generation, who have come of age in the COVID era, will experience these moments in the same sense; coupled with other social, financial and environmental crises that (perhaps naively) didn't feel quite as heavy a mere decade ago, the overwhelming feeling is that they will not.

To many millennials, the 'YOLO' days are stored somewhere in the soft vaults of our memories, but not considered a cultural artefact just yet. Cell Project Space calls the temporal context of the body of work "the early social media era", and while this is partially true, given that Facebook was founded in 2004, Twitter (or 'X') in 2006, and Instagram in 2010, we can happily concede that those were the days when social media was still fun, and not a kind of monstrously self-aggrandising, relentless branding tool. Solo Yolo harks back to the days of bringing a digital camera to a function at the weekend, before later extracting the SD card to upload all your photos to a Facebook album.

These images won't change your life; instead, they have already been your life. A personal favourite, the 'Untitled' triptych of a flimsy curtain pulled over a bedroom window with disco lights blaring from the interior, is quietly beautiful, and rooted in a nostalgia that is almost painful. Among this body of work, we see a time that is not only remembered as less anxious, but also less saturated with stimuli. Moments of silence within social and personal environments and scenarios feel out of reach now; if I'm not with you face-to-face, I am in theory endlessly available via WhatsApp, phone calls, Messenger, Instagram DMs, etc.

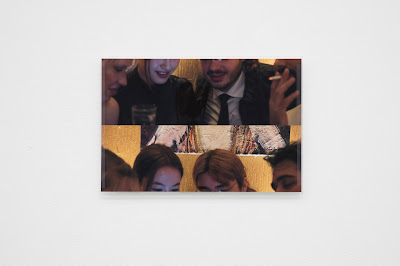

As well as providing an outlet through which to lament the recent past, Solo Yolo does speak to specific moments and people, such as in 'Playgroup' and 'Alex'. In the latter, we see presumably a friend of the artist given their own image, layered in two different states of leisurely relaxation. We don't know who Alex is, and we don't need to. They feel like someone you've just met at a party, a friend of a friend, but we can guess that they are more significant to Taleb. Similarly, we don't know anything of those captured in 'Playgroup', and yet the glare of the phone screen looks familiar, as do the vaguely content facial expressions and the rogue indoor cigarette.

Elsewhere, we find images of surfaces, such as packed desks covered in miscellaneous paraphernalia and television screens. The materiality of these works hit differently, and create a space between the photographer and the environment they are immersed in. The slanted perspective of 'Untitled', with its laptop and Hello Kitty merchandise mug angled so that they look as if they are sliding downwards off a surface, could only be viewed this way if the subject is on the floor. Is the photographer a spectre? Are they (un)conscious? Looking again at the works through this less positive conceptual lens sheds a different light: suddenly, we notice that none of the individuals captured are looking directly at the camera, nor the person manning it; these are scenes of activity and joviality, yet we as the viewer are distinctly isolated, uninvited. We see the glare of the phone reflected back onto the faces of the friends in 'Playgroup', but we're certainly not in on the joke. A screen forms a barrier between the lived experience and the viewer, and Taleb has cleverly forced this into the light by providing incomplete snippets. Not only do they allude to isolations felt during COVID and various mental and physical health crises we face as individuals and as a collective, but by being distinctly un-immersive, we are reminded that our view is only our own, and cannot be duplicated, however impactful a photography practice might be.

_1.jpeg)

+The+Sea+House+-+Suky+Best.jpg)