Jack Dartford at Outernet London

Last week was Mental Health Awareness Week in the UK, and it seems that the more the issue is discussed in circles that are neither equipped nor dedicated to grasp it in depth, the more murky and the perception of mental illness becomes. Depending on who you're speaking to, mental health can come to mean everything or nothing. By being bastardised and commercialised, often under workplace capitalism, today's salaried workers are "generously" provided with wellbeing programmes as part of their employment, but what ends up occurring is an outsourcing of negative emotion, distress and, ultimately, mental illness. As undesirable as it may already seem, this scenario is the more privileged position of being in secure work, and grappling with the more supposedly moderate manageable and common conditions such as anxiety and depression. Out of sight, out of mind!

However mild conditions are claimed to be on paper, by the authoritative voices of employers and even the NHS, each individual will experience them differently. Alas, I have always been perplexed by the glib classification of depression as commonplace and mild, given that contemporary conditions can make these health scenarios disabling. As for anxiety, although public discourse is far more comfortable throwing the word into conversation (usually to little or no avail), the condition can signify a wide range of issues, from nervousness when performing or giving a speech, to a relentless, life-altering situation that can evolve into the likes of agoraphobia (a poorly understood and decidedly unsexy branch of anxiety) . Has a widening of the conversation around mental health really given us a better understanding, or level of care?

So let us add contemporary art into the equation. The industry is not immune to adopting mental health as something of a buzzword, and it is quite rare to find an artist who works with, and communicates, mental health lived experience in a poignant and engaging way. Moving forward out of Mental Health Awareness Week, the awareness seems to be mostly around the buzzwords of "wellbeing", and increasingly "burnout", neither of which we will explore now, but aside from tips on coping strategies, there is little engaging material out there for a general audience. Meanwhile at Outernet in central London, no one could accuse artist Jack Dartford of neglecting the multi-sensory imagination with his installation Monolith. Partnering with mental health charities CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably) and ADOT, Dartford has created a site-specific interactive installation to capture the bodily experience of anxiety.

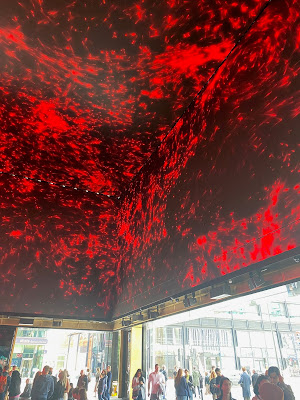

Whilst its physical setting, with an intimidatingly high ceiling, access directly from Tottenham Court Road station, and bizarrely opulent gold facade, does contribute to the experience of the artwork, the content of the piece deserves further attention. Throughout its short run, Monolith was only displayed in short bursts each day, for instance 12pm-2pm most days. Prior to arriving, I thought this to be rather withholding; why couldn't organisers show it all day? Once I stepped foot in the space, I was immediately able to answer my own question, at least from a conceptual standpoint. The idea of Monolith is an audience-sensitive reactive reproduction of the sensory and bodily experience of anxiety, with neon-esque lights sweeping across the walls and ceiling of the space, and an immersive sound element by sound designer Halina Rice aligned with the urgent movement of the visuals, as the installation starts to "panic". This cocktail is highly evocative, puppeteered by technology that is supposedly manipulated by the coming and going of the artwork's human audience, although judging by the patterns and repetition in the work, this element is less convincing.

Despite an initial cynicism about the scale of Monolith, and its location in an incredibly lively, densely populated and highly lucrative spot in London, this is a collaboration that understood its potential and knew how to work with such a unique space with impressive results. The volume of vehicle and pedestrian traffic nearby, exacerbated by the lack of doors separating the interior from the street, adds to the power of reproducing the almost claustrophobic effects of anxiety; even cold and sharp gusts of wind blown in from Charing Cross Road ensure the viewer's body remains alert and stimulated.

Official documentation images are slightly misleading as to what the experience actually looks like at Outernet. While photographs convey a high-art, 180 Studios style, the reality is not only a great deal of noise pollution to contend with, but a discovery that audience members are there for a range of reasons. Truly, this melange is what "public art" should be producing; it would be pretentious and gatekeeping to say that the people taking goofy selfies against the installation dampen the impact of the work, or have less of a right to be there. For many, the very nature of Monolith allows the subjective experience of anxiety to be given space to exist without pathologisation and, daringly, public stigmatisation. With the shame that still surrounds most mental health conditions, Dartford's work will have made many anxiety sufferers feel surprisingly seen. While public often art gets a bad wrap from elite critics and art lovers alike, the overwhelming feeling walking away from the display was that moments of liberation and clarity cannot be reserved for such a small group; this was validated by a large-scale campaign by Ironmongery Direct, which highlighted the 687 tradespeople lost to suicide every year. Mental health resides in every body, and Monolith makes this fact vividly visible.

Resources:

Ironmongery Direct's 'Mental Health in the Trades' 2023 report

Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM)

_1.jpeg)